reading-notes

Course 102, Entry 6: Dynamic web pages with JavaScript

JavaScript

At its inception, JavaScript was made for use in web browsers. It allows allows for dynamic content to be created within a website. This would be considered “client-side” running. Nowadays, JavaScript runs on servers also. The most popular version of these server languages is Node.js.

JavaScript can be included within the HTML file of a website, or it can be within an external JavaScript file, which is then imported. Examples of the lines of code to accomplish such are found both below.

Internal

<script>

alert("Hello World");

</script>

External

HTML File

The following line of script is normally found in the head section of the HTML file.

<script src="script.js"></script>

JavaScript File

alert("Hello World");

Variables

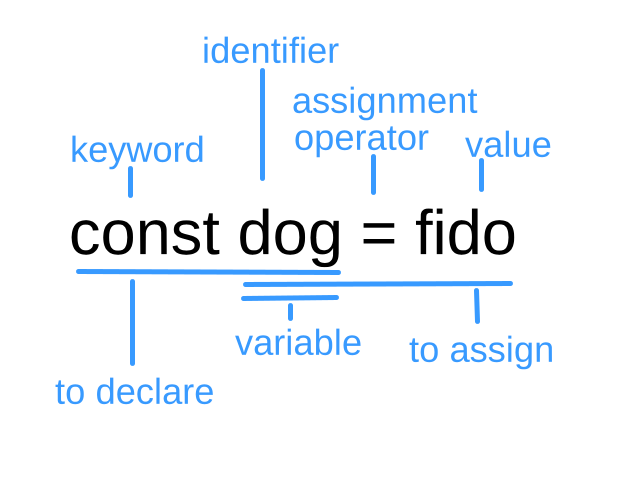

To store information, a variable must be used. When making a variable, this is called declaring. The two keywords that can be used to declare a variable are let and const. The let option is modifiable, and const is unchangeable. To declare, a unique name must be given. This is the identifier. But declaring just makes it known. To give it meaning, a variable must be assigned to some value. This is done using the assignment operator, =. Here is what this looks like.

Characters that can be used are numbers, letters, _, and $. Reserved JavaScript words can not be used. Note, letters are case-sensitive.

Data Types

Text is known as a string. If numbers and strings are added on the right side of an assignment, the system has no choice but to make the sum a string. What would be 9 + porkchop be otherwise? Note that order of operations applies. Logically, 3 + 3 + porkchop would be 6 porkchop.

Additionally, there are two comparison operators.

Abstraction comparison compares if two values are equal in concept. The inputs two and 2 are an example of this. In other words, the values are converted to the same type via type coercion before performing the comparison. Abstract comparison uses the == operator to run this comparison. A coouple odd-balls are that, "1" == true or "" == 0 will return true.

Strict comparison compares if two values are actually equal. Meaning, the two values need to be of the same type. While 2 and 1+1 are the same, two and 2 are not the same in strict comparison. Strict comparison uses the === operator to run this comparison.

Notable Examples

Among the examples to be mentioned, there are three major ways in which JavaScript interacts with the user’s computer. One is through the browser console. Normally this can not be seen unless the user right-clicks the screen and selects “Inspect”. From here, outputs can be seen in the “console” tab.

The second is by pop-up alert. This pop-up can either just be a notice, it can be a binary choice of “OK” or “Cancel” (thus a kind of Boolean), or it can ask for user input.

The third is by writing to the HTML document.

Console

console.log

The following is an example of code which will write a determined message to the console. In this case, Hello world.

console.log("Hello world.")

document.write

With document.write, code can be pulled into an HTML document. By adding other lines of JavaScript code to obtain user input in conjunction with document.write, the web page can differ depending on the input, thus making a web page dynamic. Note, document.write is not just limited to text. It can also write HTML code. Thus, any aspect of a page can change depending on user input.

The following example writes the bolded text, “Hello world.”

document.write("<b>Hello world.</b>");

Pop-up Alerts

alert

To pop up a window in which the user hits “OK” to continue, the following code can be used. The message in this example is “Only US citizens can enter.”

alert("Only US citizens can enter.")

confirm

Similar to “alert”, this is a notice pop-up which now has two options. The user can either hit “OK”, in which case they will be directed to one path (dependent on what is coded next), or the user can select “Cancel”, in which they will be directed to another, different path.

Here in this example, the confirm command with document.write has been combined. If “OK” is selected, the user gets a picture of an ice cream cone and the text, “An ice cream cone, for you.” If the user selects “Cancel”, the page will show an ice cream cone on the ground with the text “I’m so sad you didn’t want this.” Some “if, else” syntax has also been added to allow for this dynamic output. Without some code such as this, the confirm function wouldn’t be useful. Also notice, using quotation marks needs to be done carefully. In this example, to avoid syntax conflicts, apostrophes were used and no contractions were used.

if (confirm("Can I get you some ice cream?")) {

document.write('<h1>An ice cream cone, for you.</h1><br><img src="ice_cream_cone.jpg" alt"ice_cream_cone" />');

} else {

document.write('<h1>I am so sad you did not want this.</h1><br><img src="ice_cream_cone_ground.jpg" alt"ice_cream_cone_ground" />');

}

Prompt

Prompt is the way in which user input can be received via a pop-up. In order to use this input information, it must be stored as a variable.

In the following example, the user’s favorite flavor of ice cream is saved as a constant variable. This is done by assigning the identifier favorite_ice_cream to the user’s favorite ice cream, using the keyword const. The written response to the page is indiscriminate.

const favorite_ice_cream = prompt("What is your favorite flavor of ice cream?")

document.write(favorite_ice_cream + ". That's a good one.")

Similarly, a prompt can be given based on prior data. In this example, the user is asked to come up with a punny ice cream name using the current US president’s name. The president’s name being prior data. This is done by separating the data to be edited from the prompt question, via a comma. Likewise, the computer’s response is indiscriminate here.

const presidental_ice_cream = prompt("How about a punny name for President Biden's ice cream?", "Joe Biden");

document.write(presidental_ice_cream + ". Hahah. That's funny.")

Input Dependent Output

Using stored variables, another option is to respond to a previous response, such as the prior question of favorite ice cream, and asking for an update or another flavor. Here is how that would look. To do so, we need to use some if statements, combined with potential responses. Thus, if a response is equal to a coded option (equal being coded by using ==), the subsequent code runs. Otherwise, the user is asked to try again. This example does not have a loop feature. Therefore, there are only two user input runs. Note, if-else commands are localized. Thus, if any code within the blocks, including declarations or assignments, are temporary.

const favorite_ice_cream = prompt("What is your favorite flavor of ice cream?");

if (favorite_ice_cream == "vanilla"){

document.write("Ah, " + favorite_ice_cream + ". I know that flavor.");

} else if (favorite_ice_cream == "chocolate"){

document.write("Ah, " + favorite_ice_cream + ". I know that flavor.");

} else if (favorite_ice_cream == "caramel"){

document.write("Ah, " + favorite_ice_cream + ". I know that flavor.");

} else {

const favorite_ice_cream2 = prompt("Are you sure you wrote that correctly? Or perhaps there are any other flavors that you like?", favorite_ice_cream);

if (favorite_ice_cream2 == "vanilla"){

document.write("Ah, " + favorite_ice_cream2 + ". I know that flavor.");

} else if (favorite_ice_cream2 == "chocolate"){

document.write("Ah, " + favorite_ice_cream2 + ". I know that flavor.");

} else if (favorite_ice_cream == "caramel"){

document.write("Ah, " + favorite_ice_cream2 + ". I know that flavor.");

} else

document.write("You said " + favorite_ice_cream2 + "? I don't know that flavor. Hahah.");

};